Basilikos is a Greek adjective denoting monarchy, majesty, and regality. The aroma of basil is deemed so exceptional that it is suitable for a royal residence. Additionally, there exists a royal ointment in the treatise On Compound Medicines according to the Places [of the Body], authored by the Greek physician Galen (129-after [?] 216 CE), referred to as “Royal Indian” (Indikon Basilikon), in Book I, chapter 450.

The ointment is designed for the treatment of amblyopia, among other conditions, by applying it to the eyes. The formula comprises a rare and exotic ingredient, including indigo paste, which may explain its designation as "Indian," given that indigo was a prevalent product of India. In the same work, another formula is recognized as Royal (Basilikon) (Book 9, chapter 581). It is suggested for the management of edema without fever, hepatic inflammation, and neuralgia. It comprises many components, including Indian Nard, which may have warranted its designation as royal due to its rarity and expense, as it was brought from the Himalayas through India and marine trade via the Red Sea.

The true significance of the word indicates an alternative direction. In ancient Greece, the term basilikos predominantly referred to the king of Persia. The Persian Empire, located at the eastern boundary of the ancient Greek world (encompassing present-day Turkey and extending into the Middle East), was characterized by the Greeks as a hereditary monarchy, in stark contrast to their electoral democracy.

In ancient Greek, the term for king predominantly denoted the monarch of Persia, and the adjective 'royal' pertained to Persia. This politico-ideological analysis of the term basilikos reveals a link between basil and the East. Given that basil originates from India and surrounding regions, it would not be unexpected for it to have been introduced to the Greek world via the Persian Empire, which engaged in trade with the Greeks despite political and ideological disparities. This explanation is particularly plausible given that basil's medicinal profile in the Greek world was decidedly not associated with royalty or kingship. The indicators in the Hippocratic Collection, as previously said, are limited and unremarkable.

In the extensive body of ancient Greek natural sciences, there exists a serpent named basiliskos, which closely resembles the term basil. This is a poisonous snake known to lethally incapacitate its prey nearly quickly. While it may be a cobra, whose neurotoxic venom is indeed swift, as exemplified by the narrative of Cleopatra’s demise, it has attained a legendary and supernatural status, with numerous tales and legends chronicling lethal encounters that have evolved into epic literary confrontations, extending to works such as Harry Potter. However, this is undoubtedly not the etymology of the term basil. Nonetheless, poison provides insight into a view of basil conveyed by the ancient Roman naturalist Pliny (23/4-79 CE) in his extensive work on natural sciences, Historia Naturalis (Natural History).

Basil possessed a disputed reputation. In the writings of the Corpus Hippocraticum, it is not regarded as a principal medicinal agent with notable healing characteristics. It is possible that it acquired a distinctly unfavorable reputation.

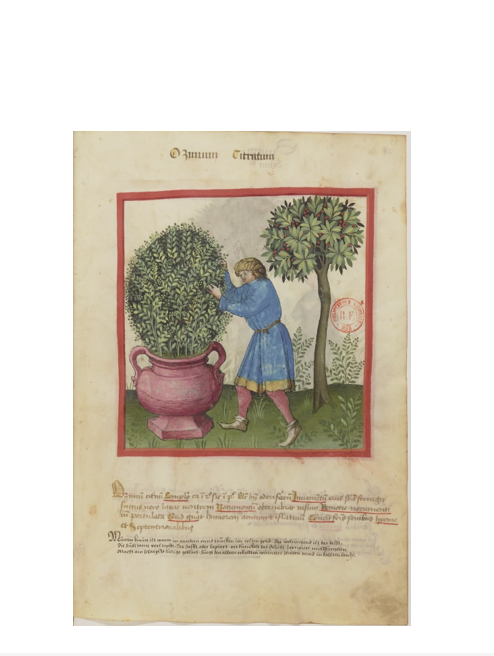

Figure: Basil in manuscript of Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Latin 9333, folio 28 recto, Tacuinum sanitates.

Ref.: AHPA, American Herbal Products Association. Available at: https://www.ahpa.org/herbs_in_history_basil